Irregular Ordination

The General Convention's 1973 vote rejecting women's ordination was a signal for many that the time had come to work outside the legislative system. Suzanne Hiatt, who had hoped to be ordained, recalled, "I realized […] that my vocation was not to continue to ask for permission to be a priest, but to be a priest." Women deacons turned to civil disobedience in their attempts to fulfill their call to the priesthood.

In New York, five qualified female deacons silently presented themselves alongside their male counterparts to Bishop Paul Moore for ordination. Moore supported women's ordination but felt unable to disobey ecclesiastical law and turned the women away with regret. As the women proceeded solemnly down the aisle, much of the congregation flocked to the back of the church to support them. Other protests followed, including an ordination service in Minnesota at which deacons Jeanette Piccard and Alla Bozarth presented themselves and, like their sisters in New York, were denied. These actions of protest provoked counter-reactions ranging from collegial discussion and debate to verbal abuse and even physical violence.

As the debate raged around them, the women began to consider the possibility of an "irregular" ordination. Eleven women, Merrill Bittner, Alla Bozarth, Alison Cheek, Emily Hewitt, Carter Heyward, Suzanne Hiatt, Marie Moorefield, Jeanette Piccard, Betty Bone Schiess, Katrina Welles Swanson, and Nancy Wittig, agreed to participate in an ordination ceremony at Philadelphia's Church of the Advocate on July 29, 1974.

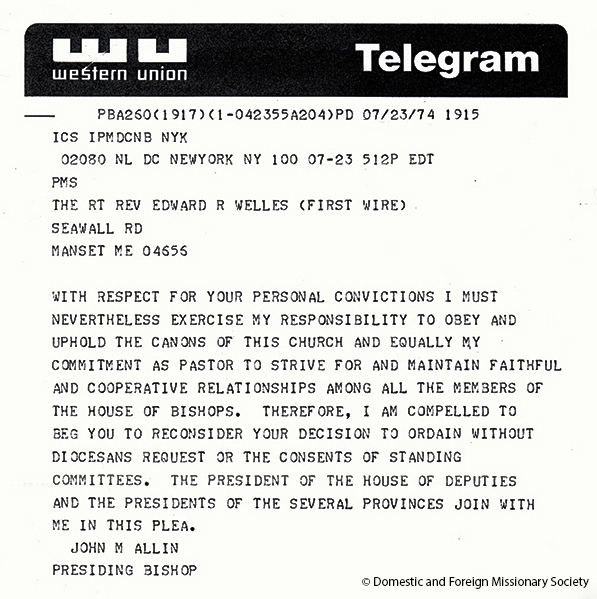

The ordination service for the women, soon known as “the Philadelphia 11,” was not planned as a protest and was not intended to be publicized. Ultimately, the women were forced to go to the press in order to present their view of the ordinations before their opponents could. In a statement published nine days before the service, they wrote, "We know this ordination to be irregular. We believe it to be valid and right... We do not take this step hastily or thoughtlessly. We are fully cognizant of the risks to ourselves and others. Yet we must be true to our vocations-- God's irresistible will for us now. We can no longer in conscience answer our calling by saying, 'eventually, when the church comes around to accepting us.'" In response, Presiding Bishop Allin sent a telegram to the eleven women, pleading, "For the sake of the unity of the church and the cause of ordination of women to the priesthood, I beg you to reconsider your intention to present yourself for ordination before the necessary canonical changes are made."

Once the ordinations were announced, all hope of an intimate service vanished. Angry letters and phone calls poured into the Presiding Bishop's office from around the country, demanding that he stop the ordinations. Despite these objections, the service was held at the Church of the Advocate, whose rector, Rev. Paul Washington, was a well-known Civil Rights activist. Amid rumors and fears of violence, the church was swept for bombs, and Hiatt, concerned for her mother's safety, asked her not to come to the service.

Three bishops, the Rt. Rev. Daniel Corrigan, retired Bishop Suffragan of Colorado, the Rt. Rev. Robert DeWitt, former Bishop of Pennsylvania, and the Rt. Rev. Edward Welles II, retired Bishop of West Missouri, presided over the irregular ordination service. The sermon was delivered by Charles Willie, Vice President of the House of Deputies. Barbara Harris, later the first female Episcopal bishop, led the procession as crucifer. A number of hostile priests stated their objections to the ordinations, and Piccard's grown sons had to be physically restrained when a member of the crowd questioned her capabilities due to her age. In spite of these disruptions, the service proceeded peacefully and the 2000 worshipers packed into the church witnessed the ordination of the first eleven women priests in The Episcopal Church.

Following an emergency meeting of the House of Bishops, Allin sent a letter to the women, explaining that the House of Bishops "would like to talk with you personally." Counseling patience while the church dealt with the issue of ordination, he advised the women that "it would certainly be important to cope as creatively as possible with your question of what to do, how to feel and how to plan personally and professionally," and offered the services of the Office of Pastoral Development “free of charge.”

Bishop Allin's letter was received with sharp indignation. Schiess replied that the only solution to her "great distress" was "a profound change of behavior on the part of our Bishops," and requested that the funds for her pastoral care be donated to a women's center. Heyward wrote that the letter struck her "harder than a slap in the face," and noted, "We have support. People throughout the Church [...] are giving us support." If the House of Bishops truly wished to support the women, Heyward wrote, "perhaps it can yet affirm [...] the validity of our ordinations to the priesthood [...]. When this is done, I will be glad to sit down with you and others and figure out how we can be supportive of each other."

Had events transpired as originally planned, the women may have been known as the Philadelphia 12. According to Hiatt, "We were aiming for twelve ordinands for obvious reasons [...] but one dropped out because she felt she was too far away and lacked support." The twelfth woman, Diane Tickell, of Anchorage, Alaska, was ordained on September 7, 1975, with Lee McGee, Alison Palmer, and Betty Rosenberg at the Church of St. Stephen in Washington, D.C.. These women, who became known as the Washington 4, were ordained by retired Bishop George Barrett, with Bishop José Ramos of Costa Rica in attendance, without the permission and against the directives of the Bishop of Washington. In response, Presiding Bishop Allin said that such "distressing and divisive acts may be beyond prevention amid this age of confusion and turmoil. The tragedy is that so much done in good conscience for the sake of renewal can so frequently prevent that needed renewal."