Deaconesses

The modern Protestant female diaconate was first introduced in Germany in the 1830s, with the foundation of the Kaiserswerth Deaconess Institute, an experiment that spurred great Anglican interest and saw a number of church leaders paying visits to the institute and returning with fresh ideas and inspiration. The role of the early deaconess filled two societal needs: it provided an avenue of work for unmarried or widowed women, and created a “permanent volunteer” workforce that could devote themselves to aiding the victims of rapid urbanization, industrialization, and war.

In England, sisterhoods were already at work in hospitals, schools, and other institutions, but the women were required to be in religious orders. In the United States, however, the distinction between “sister” and “deaconess” was initially unclear. Some sources trace the first setting-apart of an Episcopal deaconess to a private ceremony in 1845, during which the rector of New York's Church of the Holy Communion, Rev. William Augustus Muhlenberg, along with the church's sexton, bore witness as Ann Ayers consecrated her life to Christ as a Sister of the Holy Communion. Other scholars recognize the seven women who were "set apart" in 1858 to form the Sisterhood of the Good Shepherd in Maryland as the first Episcopal deaconesses.

The first deaconesses unaffiliated with a sisterhood or holy orders were three women set apart in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, in 1864. While the first deaconesses were set apart by their bishops without canonical authority or any standing outside the diocese, attempts were made to regularize their standing beginning in 1871. Opposition made this impossible until they achieved official General Convention recognition in 1892. Between 1858 and 1970, close to five hundred women were set apart as deaconesses to minister to "the sick, the afflicted, and the poor," but they were not allowed to function in liturgical roles. This disparity was cemented in 1919 when deaconesses were excluded from enrolling in the Church Pension Fund on the grounds that they were not clergy.

That the church understood the importance of professional women workers, though it was not yet ready to accord them any institutional power, was clear from the increasing number of church training schools and institutes for laywomen throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries. Schools specifically for training deaconesses, such as The New York Training School for Deaconesses and The Church Training and Deaconess House, were founded in 1890, with other similar schools opening across the country. As interest in church work grew, the deaconess programs expanded to include women who were not called to take the vows of a deaconess but still sought higher education.

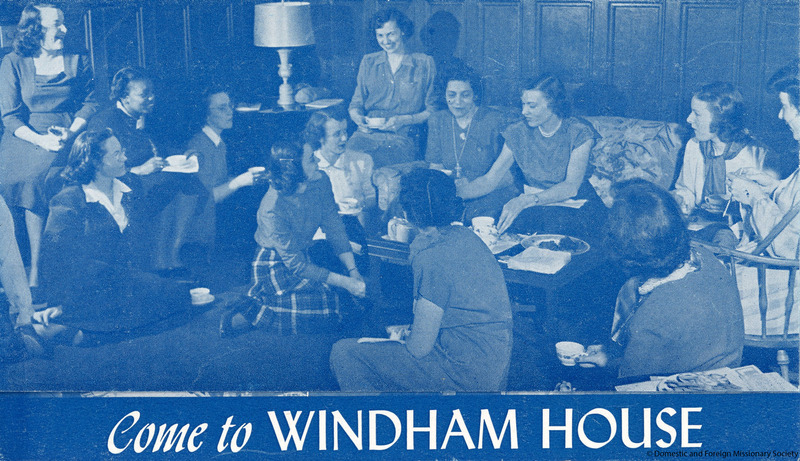

An pamphlet for Windham House, a deaconess training school, undated.